This Torah portion consists of the Song of Moses and a brief epilogue in which Moses is commanded to go to the place where he will die.

The song, as you will recall from last week, is designed to be a testament. The Israelites are commanded to memorize it so that when they turn astray and are conquered and exiled, they cannot accuse God of having abandoned them. The song is meant to be evidence that God warned them that they were going astray. Moses tells the Children of Israel to teach the song to their children and have everyone sing the song so that it becomes a pervasive theme for them in the Promised Land.

In the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, we sing Pleyel's Hymn during the MM degree. In a Royal Arch Chapter, there are a lot of songs, and in our history, Masonry has often used music lyrics to instruct candidates. The Psalms are usually sung in Jewish worship, and the Bible has a lot of songs in it. The Song of Moses is meant to be pedagogical and prophetic in nature, warning the Israelites not to go astray, while predicting that they will.

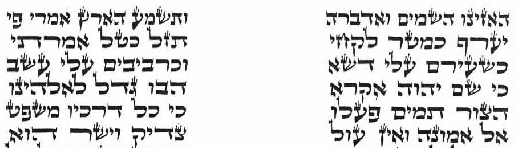

If you look at a Torah scroll, the Song of Moses is written in two columns, making a striking pattern in the text. You will recall that the Song of the Sea has a brick-like pattern when written in a Torah scroll. I have heard that Orthodox Jewish children are taught the Song of Moses as the first verses of scripture that they learn, and yet, I am unable to find a tune for these verses.

In the song, there is a couplet: "As an eagle stirreth up her nest, fluttereth over her young, spreadeth abroad her wings, taketh them, beareth them on her wings: So the Lord alone did lead him, and there was no strange god with him." [Deuteronomy 32: 11-12].

The eagle as a symbol of God bears some explaining. While we regard the eagle as a bird of prey, swooping down and tearing prey to pieces, the Israelites noticed how tenderly the eagle takes care of her young, carefully tearing strips of meat for the eaglets to eat, and placing the nest safely in remote perches. Earlier in Exodus 19: 4, God tells Moses to tell the Children of Israel: "Ye have seen what I did unto the Egyptians, and how I bare you on eagles' wings, and brought you unto myself."

The eagle appears in alchemy and haut-grade Masonry. Indeed, the double-headed Eagle of Lagash is the symbol of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. In alchemy, it is a symbol of whiteness, or the transmutation of base metals into fine metals. The eagle is also a symbol of the sign of Scopio, along with the fish and the scorpion. To describe the Deity as an eagle is very striking, but in context it is used to show the protective nature of the Deity, and the power to transport us to safety.

And yet, we can fail so badly that God will hid His face from us. The early Hasidic masters understood this to mean that not only would God hide His face from us, God would hide the hidden traces of His existence. We exist in a world where God is hidden. But a world where what is hidden about God is hidden from us is terrible, indeed. The Sufis understood that longing for God was a sacred emotion. In a world where the hidden face of God is hidden from us, there is the terrible peril that that longing might disappear, leaving nothingness in its wake.

" They have moved me to jealousy with that which is not God; they have provoked me to anger with their vanities: and I will move them to jealousy with those which are not a people; I will provoke them to anger with a foolish nation." [Deuteronomy 32: 21]. In the Hebrew, there is a verbal wordplay between the non-God and the non-nation. When we worship something less than God, we become less than people.

The song ends by saying: "Rejoice, O ye nations, with his people: for he will avenge the blood of his servants, and will render vengeance to his adversaries, and will be merciful unto his land, and to his people." [Deuteronomy 32: 43]. This is a strange consolation. After verses of admonition, there is half a verse of mercy, and we are called upon to rejoice.

But the bitterness does not end there, for after Moses finishes the song, God calls him to Mount Nebo, to lay down his body and die. He tells Moses to look across the Jordan River at the Promised Land, but because he struck the rock at the Waters of Meribah, his punishment is to be that he never got to set foot in the Promised Land.

The Torah is nearly completed, and I will have more to say next week about the ending. I find it very strange that the narrative ends on such a bittersweet note, with the ungrateful Children of Israel getting a home while Moses is doomed to die alone in the clefts of the rocks.

‘Washington inauguration celebration’

5 hours ago

No comments:

Post a Comment